“Ensuring that ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO) is Adaptive and Resilient” was the topic of a workshop organized on 5-6 June 2019 (Brussels) by the MIREU project, in collaboration with the H2020 projects NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA. Approximately 50 participants with highly diverse backgrounds coming from academia, industry, government and civil society discussed the drivers and barriers, and the opportunities and pitfalls of the SLO-concept. The workshop included several sessions in which the global and European context, the rules of engagement and the way forward for SLO were analysed. The present article reflects upon the key lessons learned from the high quality presentations and the lively debates. (Leuven, 25/06/2019) (Author featured image: Julien Harneis**).

Rationale for workshop

Faced with the consequences of climate change, the transition to a low-carbon economy is ever more urgent (Jones, 2018). This transition requires a large amount of Critical Raw Materials (CRM), such as the rare earths neodymium and dysprosium, as well as lithium and cobalt. Currently, primary mining is not always conducted in the most environmentally-friendly way. However, as recycling efficiencies are still low and insufficient to cover the current demand for a number of key metals for clean energy and mobility, primary mining is required to support this transition.

The mining industry is often confronted with a negative reputation in society. In many cases new exploration or exploitation activities of mining projects create opposition and social conflict. The general public, especially in western countries, has a rather negative view on mining. This is paradoxical as western consumers largely depend on the mining industry to provide the necessary materials for the comforts of their daily lives. There is a general perception – both amongst European citizens and on a global level – that mining is a high impact activity. Resistance to mining varies from raising valid environmental concerns to outright ‘Nimby-ism’ (Not In My Back Yard). In any case, lack of social acceptance can hinder the development and implementation of any mining activity.

The main questions are then: how can we produce the minerals and metals we depend upon in the best possible way? Which environmental, social, health and safety risks are we willing to take? Who will bear the biggest burden? Which potential lies in increasing recycling efforts? These questions formed the background for the third workshop on Social License to Operate: ‘Ensuring SLO is Adaptive and Resilient’ (June 5-6, 2019).

Opening

In his opening address, Wolfgang Reimer (Managing Director, Geokompetenzzentrum (GKZ) Freiberg) questioned whether a sound SLO process is part of a future oriented vision, or rather tends to become a utopia. Bernhard Cramer, the Saxon ‘Supreme Mining Officer’, pleaded in the first session to increase the awareness of the general public of our common mining history as a primary economic sector. Mining is per definition tied to a specific place where the resources can be found. It requires a high investment but only offers a postponed ROI for the investor. The legal certainty is a prerequisite to reduce the risk level of the investment. However, new mining projects are generally faced with an initial resistance to change. The local population should be involved from the onset (strategic planning) instead of later on, when they can only react to what has already been decided.

Mining and recycling in Europe

Europe’s mining sector aligns itself with the sustainability agenda through concepts such as the circular economy, the coming energy and resource transition, a zero-waste economy, etc. Ironically, these concepts also cause misunderstandings within society, most notably that no more mining or smelting will be needed. This can be seen in the current debate on the ban of lead, i.e. lead is a necessary carrier element for many CRMs and lead-metallurgy is fundamental for a true circular economy (Malfliet, Blanpain, & Reuter, 2019). In his presentation, prof. Markus Reuter put the concept of circular economy into perspective: “The circular economy is a beautiful concept but let’s not destroy it with half-truths.” Currently, we cannot close the loops completely as there are inherent losses in the different processes (cf. Second Law of Thermodynamics). Reuter invites companies to inform society about the real recycling rate of a product, e.g. through a label (similar to the energy label).

In his presentation of the SCALE project, Ugo Miretti showed that SLO is important not only for mining but also for secondary raw materials processing. For this type of projects, an additional challenge is the access to markets and the societal acceptance of a product based on “waste”. This sparked a discussion on the boundaries of SLO of a production process versus the societal acceptance of an end-product.

Ian Thomson of Shinglespit Consultants emphasized that SLO is deeply embedded in the mining industry. The concept has increasingly gained a lot of attention in recent years. Meanwhile, the industry recognizes SLO widely as a crucial issue; recently Ernst & Young identified SLO as the number one risk factor for the global mining industry (Mitchell et al., 2018). It is important to consider SLO from the start – many mining operations fail due to problems created at the start (by small companies from far away, with limited resources, and low expertise or interest in involving locals – by the time sufficient resources are allocated, problems have arisen and can hardly be fixed). In the past, the social contract of the mine was largely based on job creation. With the technological evolution, this is less and less the case – what is the “quid pro quo” for locals?

Entering into the company-community relationships, Prof. Palma-Oliveira considers that both science and technology are produced as part of a specific value system. This value system is inherently connected to our beliefs and implies a relation to the power structure. In dialogue with local communities, mining companies usually present the output, while it is equally (if not more) important to present the process itself. Prof. Palma-Oliveira presented a case in which scientific experiments were co-designed with the community instead of explaining the technology to the community (Palma-Oliveira, Trump, Wood, & Linkov, 2018). (Pro-)Active involvement of communities at an early stage in the exploration process is crucial. As such they can be included in decision-finding processes. A long term SLO can be strengthened if locals residents are actively engaged in an environmental monitoring activity.

In the debate, it was emphasized that ‘SLO’ refers to a relationship: it reflects a process, not a product. Therefore, an ‘SLO’ takes time. Also, the difference between an SLO at societal versus at community level was emphasized. At the same time, distinction needs to be made between the acceptance of a product and the acceptance of an activity. General awareness raising about mining activities, the impact they generate and the origin of the resources of our products was considered to form a necessary but insufficient condition for SLO.

SLO in the global context

Does SLO help or hinder mining in Europe, China, and Australia? Is Europe a front-runner in SLO or is it a suicidal strategy for industry? Those were the main questions discussed in this session, moderated by Eberhard Falck, Vice President, INTRAW International Raw Materials Observatory. He noted that, generally, local attitudes towards mining contradict the increasing need for new sources of metals and minerals. In Europe, we seem to tacitly accept that mining has to take place elsewhere. Mining and impact risks are displaced to other regions of the world where possibly less stringent controls are in place.

According to Meng Chun Lee, Project Engineer at GKZ, the main approach in China is to improve regulations when issues arise. Measures are taken to increase transparency and public participation. The issue of SLO is taken seriously by the government, for whom resource security is a top priority.

Simon Michaux, Senior Scientist at GTK, alerted that the business model of mining has changed: “With the ore grade decreasing, the size of the mining operations, the energy required and the required capital investments have increased steadily. Mining companies are now partners in their own business. The mines they operate are controlled by shareholders outside the company, and have become strategic assets part of geopolitical lobbying. Multinational companies try to control the integrated value chain from mining/recycling, smelting, to manufacturing. They advocate with governments to build complementary infrastructure for their operations and often negotiate (or even coerce) beneficial tax deals.”

In the past, Europe purchased its primary materials from other continents. The EU28 is now challenged to source its own materials by developing its own mining and minerals. Considering that most of Europe has not been surveyed below a depth of 100m, it probably holds several world class deposits. However, these deposits cannot be developed using conventional mining methods. Michaux believes that “until people understand the link between a phone and a mine, it is likely that mining will not happen in EU”. He added that the trustworthiness of the public authorities is equally crucial.

During the debate it was stressed that a fundamental social evolution in terms of demand is necessary. Complementary education and awareness raising on the production processes and on the link between production and end-product, can stimulate European acceptance and simultaneously decrease the demand. The value chains need to be more integrated and become more transparent. Demand for materials needs to be drastically reduced and mining activities need to go hand in hand with recycling striving towards a circular economy.

SLO as rules of engagement

In this session it was questioned whether SLO can or should provide a framework complementary to the existing legislation. An SLO framework or regulation should allow or stimulate society, government and industry to work together to prevent and/or solve issues. At European level, there is a high heterogeneity of national legislations. There is no SLO policy in place yet.

Michael Hitch (University of Talinn) described SLO as a relationship in which (social) legitimacy, credibility and trust are key issues. An SLO is embedded in a specific narrative and worldview, and requires sensitivity about the relational power structure (Hitch, Lytle, & Tost, 2018). It is highly context dependent and in order to be successful, both the community and the company need to contribute (e.g. honesty, willingness, openness for dialogue, etc.). Finally, it is crucial that a company can also accept a no-go decision.

Considering SLO as a relationship, Johannes Drielsma (Deputy Director of Euromines) compared a positive SLO with ‘love’. Just as is the case with ‘love’, SLO is also difficult to define, but we recognize it when we see it. The raw materials sector has a bad reputation and appears not so ‘loveable’ in society. Continuing the metaphor, various implicit rules and cultural norms define what can (not) happen in a loving SLO relationship. Laws, regulations and expectations about marriages differ from country to country, but conforming to societal laws does not imply there is actually a loving relationship. Finally, one can ask who pays the alimony in case of a divorce.

Charlotte Christiaens (General Coordinator of CATAPA) emphasized that the short, medium and long term environmental, economic and social impact of mining activities should be considered carefully. She pleads for a stronger focus on recycling, and supports the idea of including minimum SLO-criteria in EU Policy.

Patrick Nadoll (Senior Advisor on Exploration and Resource Assessment of EIT Raw Materials) stressed that (student centered) education is the key to reach a critical mass and consequently to create change in society.

During the debate, the ‘right to veto’ from local communities was discussed extensively. While popular referenda and EIA discussions (in which this ‘veto’ could be voiced) are specific events, an SLO is an ongoing relationship with highs and lows. Many mining companies have integrated SLO in their core functioning, and consider that they need to create benefit for all their stakeholders, incl. local communities. In order to deal with the wider impact of mining activities, Pedro Antonio (UN) suggests to move from ‘SLO’ to ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’, SDLO (Pedro et al., 2017).

The way forward for SLO in the EU

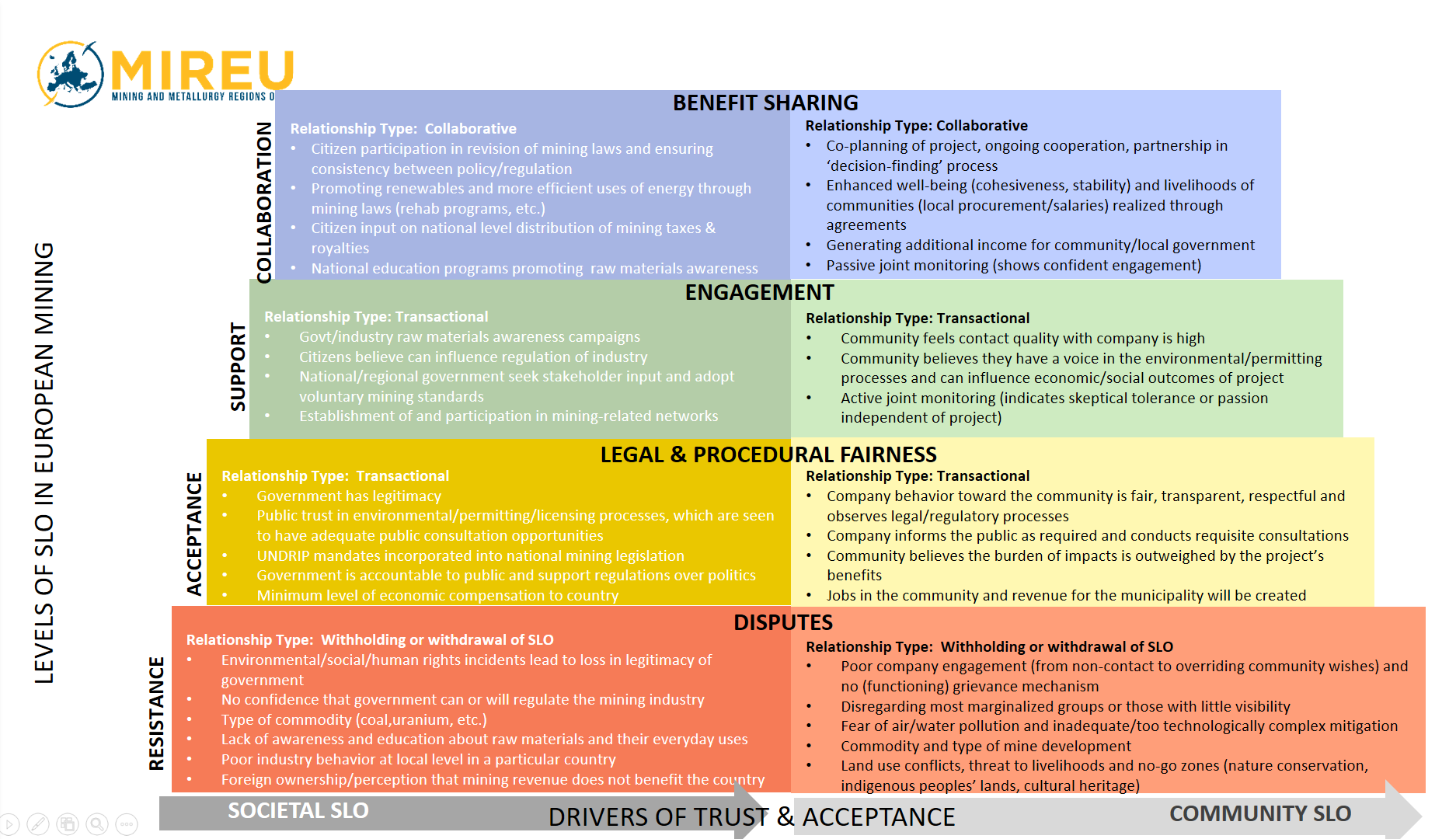

In this session, Pamela Lesser (University of Lapland) presented a brief keynote on “The state-of-the-art of the research on ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO)”. Based on the experiences of the Mireu project, she introduced the main drivers, barriers and key on-going challenges of the SLO concept. She presented the ‘Mireu-model’ in which distinction is made between an SLO on community level and on societal level (see Figure 1). Key drivers for SLO are legal and procedural fairness, confidence in governance and distributional fairness (on societal level), and contact quality perceived procedural fairness and social benefits (on community level). Finally, she also posed the question whether SLO can be beneficial for Europe’s mining industry and increase the responsiveness to local community concerns (Lesser, Suopajärvi, & Koivurova, 2017). In conclusion, the way forward for SLO is to prioritise the incorporation of a more comprehensive, multi-phased concept.

Figure 1 The MIREU model identifies four levels of SLO.

In an interactive session, the participants further debated the main insights from the keynote presentation. Several statements were presented to trigger a discussion:

- “The SLO concept is too vague and ambiguous: it should be abandoned.”

- “The government processes and procedures for public participation are enough to achieve SLO.”

- “Local communities miss the necessary knowledge to understand the company’s operations.”

During the debate, the following was reiterated:

- SLO is a process, not a product; it is a relationship which requires flexibility. It is an umbrella-concept which covers various different sub-ideas or context dependent aspects.

- Awareness raising about the link between the input material (e.g. lithium batteries, rare earth elements) and the end product (e.g. smartphone or windmill) is needed. The high and increasing demand for materials is unsustainable and should decrease.

- European government support for mining is a necessary (but insufficient) condition for companies to be able to gain SLO – without clear acceptance from government people will not accept it either. An improved view on the raw materials sector (societal support) can be supportive but is not sufficient to obtain the SLO on the local level. This commitment from ‘the top’ can be complementary to the push from ‘the bottom’.

- ‘Local communities’ are very diverse. When discussing SLO, it is challenging to identify the legitimate spokespersons. Their technological background might be limited; through the dialogue capacity building processes can allow for a better understanding of the industrial processes. External NGOs can bring in specific expertise.

- The figure of an ombudsperson could facilitate the relationship between local communities and companies. Preferably this is not one person but an independent/impartial committee; trustworthiness and competence are key. The trust in government authority and institutions varies according to local and national context.

- Funding mechanisms for community involvement and independent support must be carefully considered.

- If social conflict arises and persists, a government should be able to revoke mining licenses and concessions. There is some hesitancy from industry to include SLO in legislation – the implications of a possible veto right from a local community needs to be further debated.

- Currently, SLO seems to focus on social impact, but it does not necessarily entail sustainability. It is suggested to consider instead of ‘Social License to Operate’ rather a ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’. A broader debate about sustainability and the boundaries of the current economic system can be complementary.

- Similar procedures as for responsible research and innovation might be relevant for SLO.

- Organizing citizen science experiments might be a good way of engaging with the local communities. It can involve deliberative democracy principles and experiment with new democratic models. Participation should be encouraged; pitfalls must be avoided. Co-creation and co-design are aimed for. People want decision-finding power, not decision-making.

- So far, there is no European policy on SLO.

Lessons learned

L1. Link production processes and end product

Broad awareness raising of the general public on the production processes and manufacturing is needed. On the one hand, people need to be able to link the end product they use with the resources needed to produce it. Where does our smartphone come from? What does it take to build an electric vehicle? How many different materials are included in our laptops? When people obtain more knowledge about this, the awareness about our (high and increasing) impact on this planet will increase. The production of the raw materials we want for the applications in our daily lives should become part of the equation. If we understand what it takes to produce these products, the general perception of the mining and recycling industry might change. Possibly the societal acceptance of these industries might improve, and/or consumer behaviour might change (e.g. consume less, recycle more, etc.). Such awareness raising could stretch beyond acceptance and induce critical questions regarding the demand of raw materials.

L2. Distinguish between end product and production processes

On the other hand, a clear distinction must be made between the production processes and the end product. We need to differentiate between the production of the raw material and the final products we use in our daily lives. Understanding that society needs huge amounts of e.g. copper or cobalt, does not imply that we can accept industry to produce these at any cost. The local and societal level must be considered separately. The way how the raw materials are being produced is most primordial and will ultimately allow for a company to obtain (or not) a ‘Social License to Operate’. The societal acceptance of a certain product does not imply the acceptance of the production activity, or the way how the product is produced locally. Hence, an increasing societal demand for lithium, for instance, does not legitimize operations without the SLO. The mining and recycling sector must continue to reduce risks and increase their efforts to develop more comprehensive and environmentally-friendly production processes.

L3. SLO reflects a long term relationship

SLO is a process, not a product. It is a long term relationship between various actors. Trust, honesty and transparency are key for a successful outcome. SLO entails a dialogue between legitimate partners who respect and listen to each other’s ideas and perceptions. In this relation, it is necessary to consider ‘objective’ knowledge of e.g. an impact study as important as the ‘subjective’ interpretation or perception (e.g. how was the study conducted, who was involved, how were calculations made, etc.). When companies present the output of their industrial operations, like e.g. the production of copper, also the subjective perception of these operations matters to obtain the SLO. How this output was reached, is equally important as the process of the interaction between local communities and companies.

L4. There is no European policy on SLO yet

There is no European policy on SLO. National legislation on the minerals production differs largely between countries. Overarching guidelines and/or regulations are needed, including on the SLO concept. The European Commission, along with the European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials, has fully endorsed the SLO concept. However, more research on e.g. the operationalization of SLO and the relation between knowledge production and acceptance is needed to integrate a clear strategy on how civil society will be engaged in order to build trust in the mining and recycling sector in Europe.

(PW, 25 June 2019 – SIM² KU Leuven SLO Team)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the EU H2020 MIREU project for the excellent collaboration; all presentations given during the workshop are available on their website.

The NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects have received funding from the European Union’s EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under Grant Agreement No 776846 (NEMO – https://h2020-nemo.eu/), GA No 776473 (CROCODILE – https://h2020-crocodile.eu/ ) and GA No 821159 (TARANTULA – https://h2020-tarantula.eu/).

References

Hitch, M., Lytle, M., & Tost, M. (2018). Social licence: Power imbalances and levels of consciousness – two case studies. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment, 0(0), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480930.2018.1530582

Lesser, P., Suopajärvi, L., & Koivurova, T. (2017). Challenges that mining companies face in gaining and maintaining a social license to operate in Finnish Lapland. Mineral Economics, 30(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-016-0099-y

Mitchell, P., Downham, L., & Van Dinter, A. (2018). Top 10 business risks facing mining and metals 2019-20. 16.

Moffat, K., Lacey, J., Zhang, A., & Leipold, S. (2016). The social licence to operate: A critical review. Forestry, 89(5), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpv044

Palma-Oliveira, J. M., Trump, B. D., Wood, M. D., & Linkov, I. (2018). Community-Driven Hypothesis Testing: A Solution for the Tragedy of the Anticommons: Community-Driven Hypothesis Testing. Risk Analysis, 38(3), 620–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12860

Pedro, A., Ayuk, E. T., Bodouroglou, C., Milligan, B., Ekins, P., & Oberle, B. (2017). Towards a sustainable development licence to operate for the extractive sector. Mineral Economics, 30(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-017-0108-9

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the private views of the author and may not, under any circumstances, be interpreted as stating an official position of any of the organisers of the SLO Workshop.

**Featured Image

Wolframite and Casserite mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Author: Julien Harneis from Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo – URL)